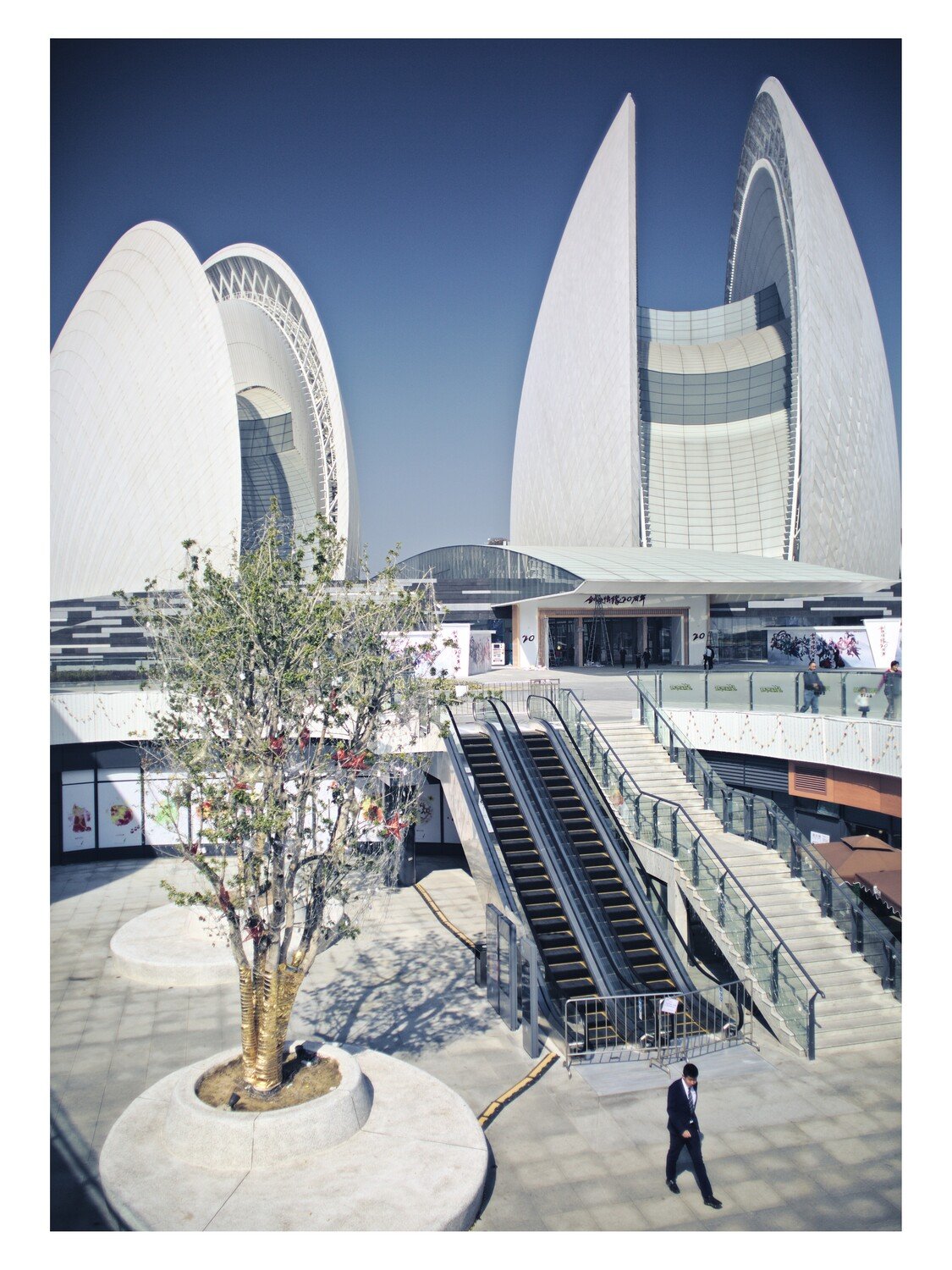

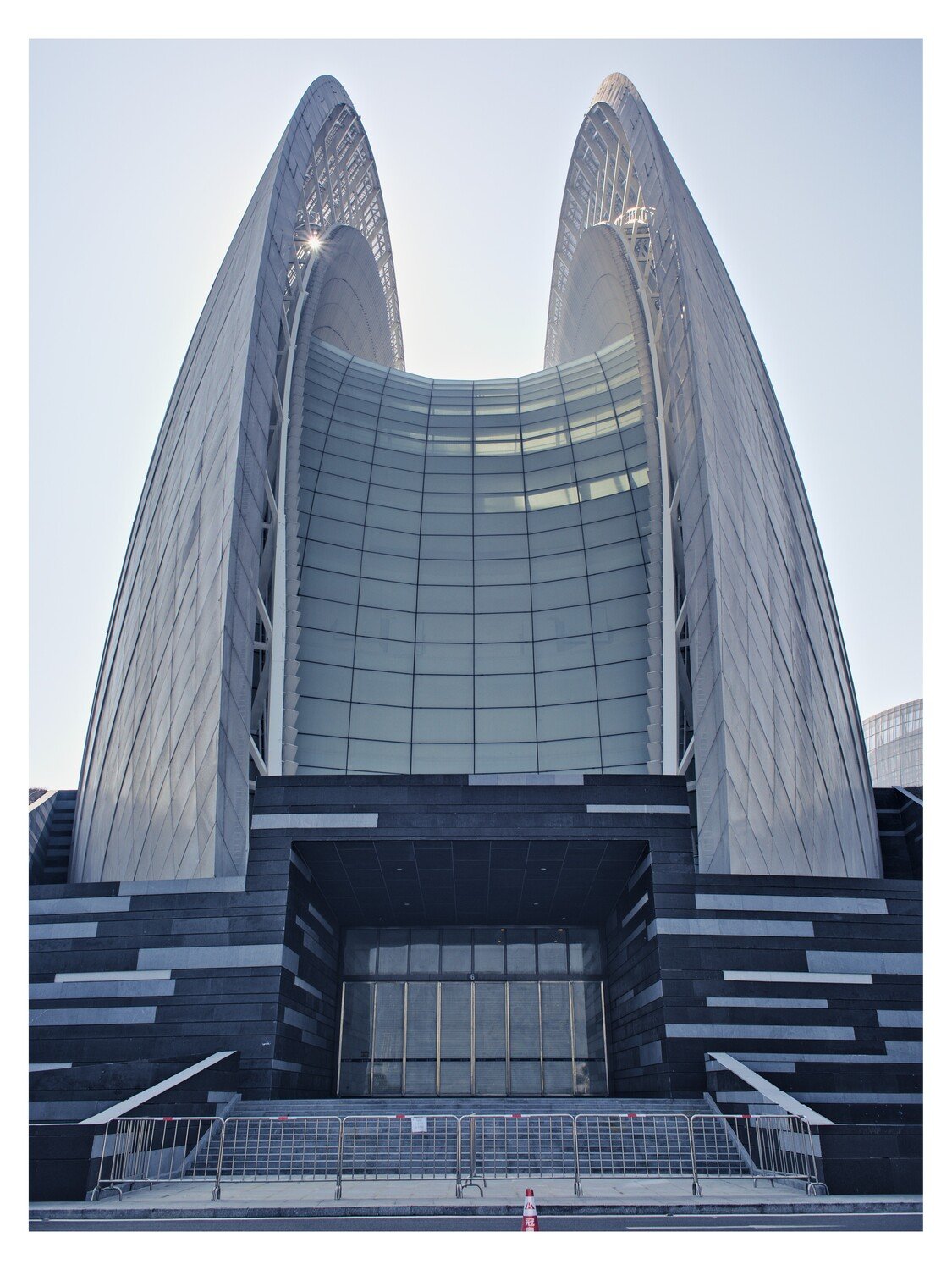

The Zhuhai Grand Theatre is often mistaken for a Zaha Hadid project, and it’s easy to see why. Flowing forms and bold volumes avoid any rectangular structures resulting in an unforgettable landmark. Located on reclaimed land and surrounded by Zhuhai bay, the design of the theatre, also called the Zhuhai Opera House, mimics the shape of seashells.[1] Parallels could be drawn to the shell design of the Sydney Opera House.

Rather than a well-known global architect like Zaha Hadid, the Opera House was designed by a local studio led by Chen Keshi, (sources differ on the principle architect) and construction began in 2010. The Opera House was completed in time for its first performances in early 2017.[2, 3] Aside from the performance venues inside the towering clamshells, the complex also includes two low-rise buildings for cultural and commercial use.[1]

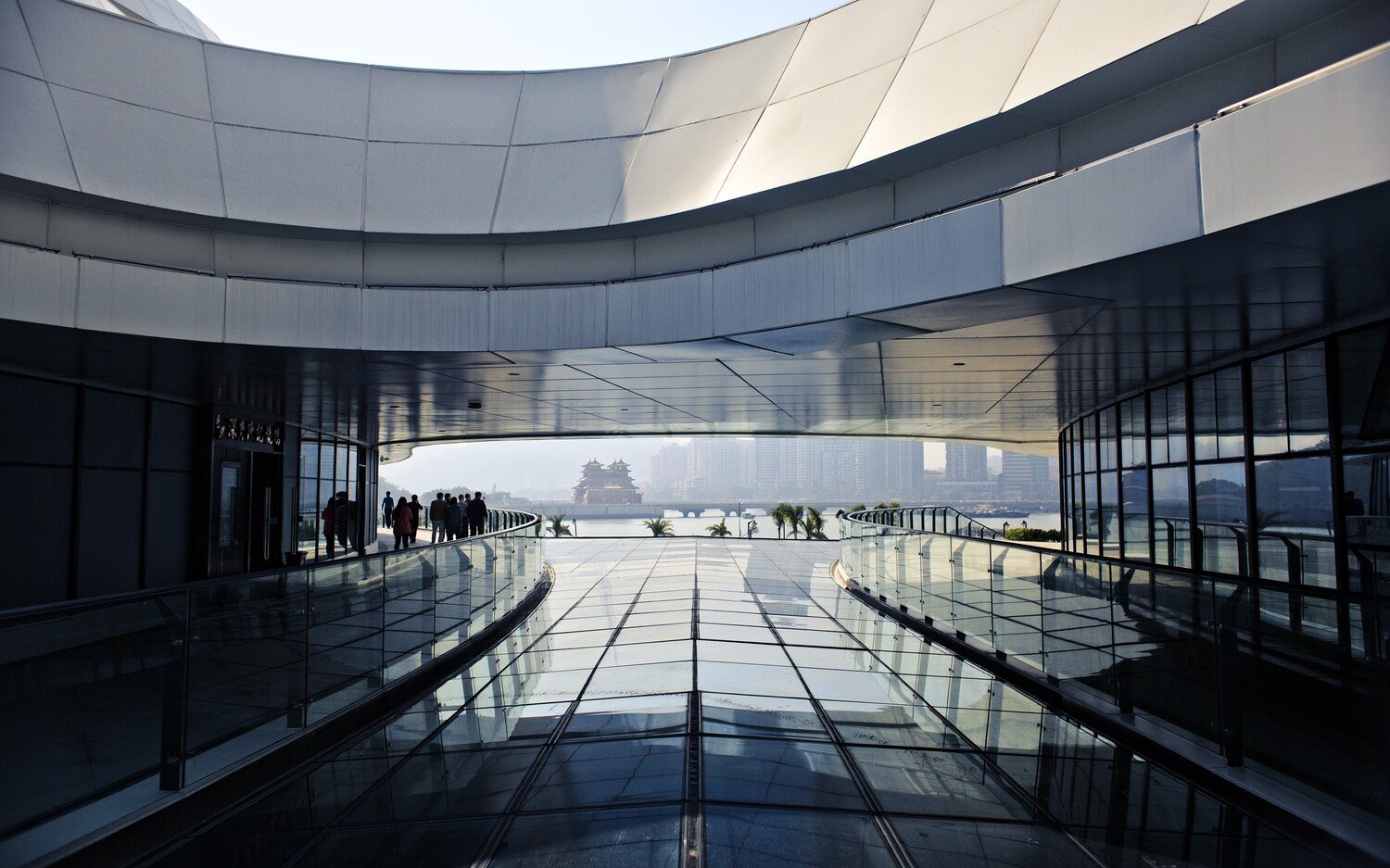

In spite of the fanfare and potential of the Opera House, a site visit one year after opening found it underused and unfinshed. The cultural and commercial spaces were nearly entirely vacant aside from one store. Construction materials were piled up around the Opera House with some areas obstructed by barriers and caution tape. Walkways and plazas were marred with broken pavement and disjointed from the adjacent road as if an earthquake had shifted relative elevations at the site.

Comparable to some other influential buildings such as the Oslo Opera House [4, 5] and the Moesgaard Museum, [6] the design of the Zhuhai Grand Theatre features a walkable green roof space at the base of the venue. This kind of accessible form extends the ground plane and the surrounding plazas onto the building which enriches visitor interactions with the structure. [5, 6] Creating additional interest for casual visitors allows the cultural landmark to blend into public space rather than be an alien form detached from it. This accessible roof, despite appearing finished, was also completely barricaded preventing it from being accessed as intended.

This failure to allow the architecture to fulfil its natural potential is not surprising, since the overuse of barriers and preference for control over activities in public space are just some of the frequent challenges that plague architecture and urban design in China.[7, 8] Lastly, it has been noted that the vast majority of the population of Zhuhai would not be able to afford the ticket price for an event at the Theatre, which indicates that it is not a cultural center for the common citizen.[1] If that is the case then the Opera House is then just another showcase project designed for appearances[8] just like innumerable other monuments to the orotund found all over East Asia.

Zhuhai Opera rises out of the sea. Macauhub. Published online February 21, 2014.

Welch A. Zhuhai Opera House, Guangdong, China. e-architect. Published online July 26, 2018.

黄珏. 珠海人正享受大剧院带来的美好生活. 金羊网. Published online January 3, 2018.

Oslo Opera House | Snøhetta. Arch2Ocom. Published online March 21, 2016.

Owen D. The Psychology of Space. The New Yorker. Published online January 21, 2013.

Keskeys P. Blended Landscapes: A New Union Between Architecture and the Earth. Architizer Journal. Published online October 29, 2015.

Nguyen NM. Towards the making of user friendly public space in china: An investigation of the use and spatial patterns of newly developed small and medium-sized urban public squares in guangzhou and shenzhen. Victoria University of Wellington. 2017.

Pu M. Brave new city: Three problems in chinese urban public space since the 1980s. Journal of Urban Design. 2011;16(2):179-207.